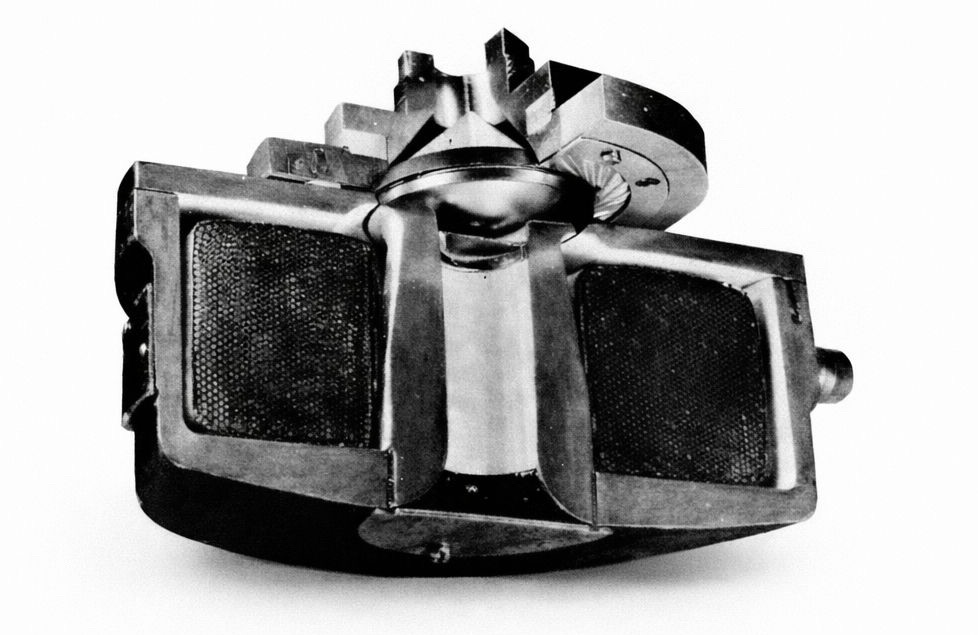

So here we start some rear chamber tuning of Western Electric 555 drivers, an important step before installation on 13Audio horns across various projects around the planet. This is the calm-before-the-storm phase, where patience is mandatory, screwdrivers are dangerous, and enthusiasm must be kept on a very short leash.

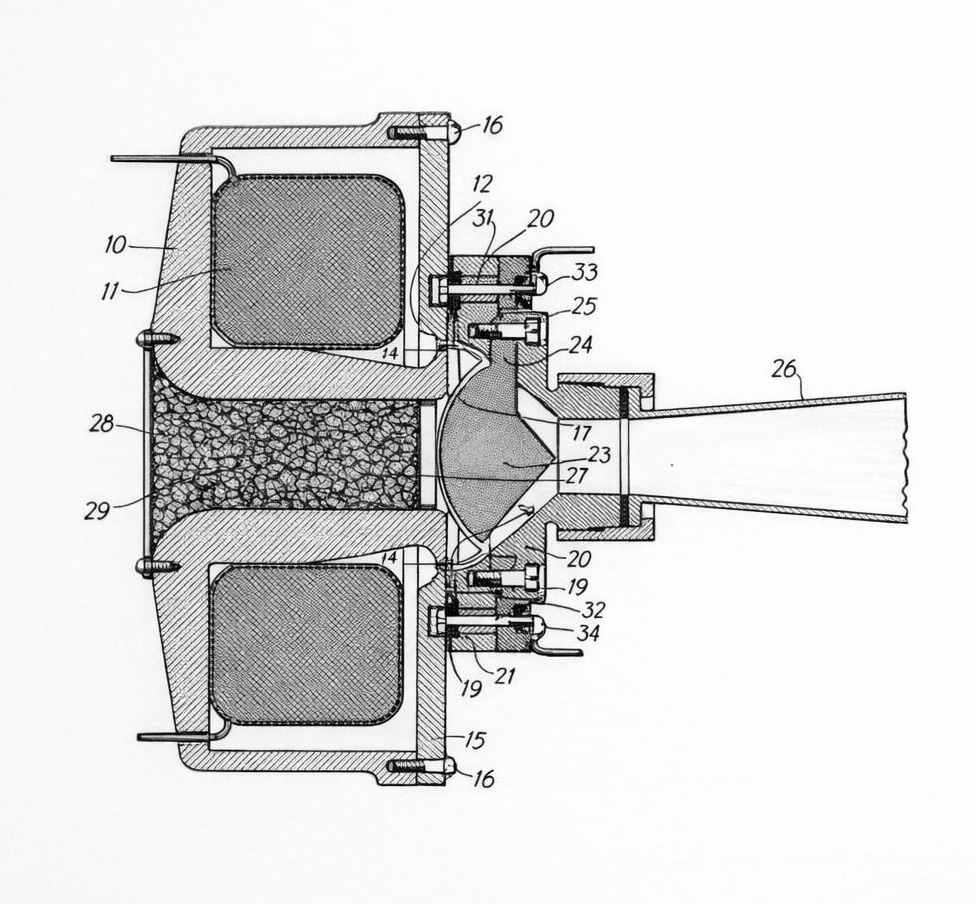

Tuning a Western Electric 555 is like adjusting a vintage watch: breathe slowly and don’t get clever. The purpose isn’t to make it bigger, louder, or more impressive — it’s to keep the diaphragm calm, controlled, and honest. The rear chamber is a delicate part of that balance. It controls acoustic compliance, low-frequency cutoff, and damping, and plays a central role in how the driver behaves. It is not there to add bass, but to stabilise the diaphragm and shape the lower midrange. Western Electric deliberately chose a relatively small, well-damped chamber to prioritise intelligibility, consistency, and control in real working conditions.

Small changes have large effects. Altering the rear volume by even 10–20% is clearly audible. Too small and the sound becomes tight, nasal, and shouty; too large and articulation begins to soften, with a loss of precision. Damping is essential and must be applied sparingly — typically felt or natural wool on the rear wall only. More is rarely better.

A resistive rear chamber, whether achieved through mesh, restricted airflow, or carefully chosen materials, adds controlled acoustic resistance behind the diaphragm. This resistance damps rear-wave energy, smooths impedance behaviour, and limits uncontrolled diaphragm motion without fully sealing the chamber. It offers a middle ground between open and sealed designs, trading a small amount of efficiency for stability and predictability.

Using a blank plate instead of a rear mesh creates a fully sealed rear chamber, offering maximum control and predictable damping. This choice is especially relevant today, as modern amplifiers can deliver far more low-frequency power than the 555 was ever designed to handle, easily driving excessive diaphragm excursion. A sealed chamber limits low-frequency movement, reducing distortion and protecting the diaphragm, at the cost of sensitivity and low-end extension.

All of this must be considered alongside crossover design, slope, and turnover frequency, which ultimately decide how much low-frequency energy ever reaches the driver. When it suddenly sounds effortless, stable, and unforced, stop. Tools down. Walk away. That’s not unfinished — that’s success.